|

|

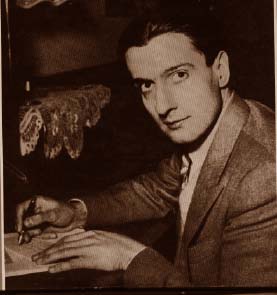

Born Bucharest, (Romania) 1917; died Geneva,

1950.

Born into a musical family, he was the

godson of George Enescu. At the age of four he performed at concerts for

charity and began composing. He entered the Bucharest Conservatory under a

special dispensation, where he studied with Florica Musicescu. Alfred Cortot

resigned in protest from the jury at the Vienna International Competition in

1933, when it awarded Lipatti only second prize. In that year Lipatti moved to

Paris to study with Cortot and Yvonne Lefebure (piano), Charles Munch

(conducting), Paul Dukas and Nadia Boulanger (composition). Concert tours of

Germany and Italy in 1936. First recordings, of piano works by Brahms, in 1937.

From 1939 he stayed in Roumania, giving many concerts, but fled to Geneva in

1943, with his future wife, the pianist Madeleine Cantacuzene. Severe illness

forced him to reduce his concert work drastically, and to refuse major tours of

the USA and Australia. He turned to composition and more recording. Lipatti 's

pianism is an ideal synthesis of a composer's analytical insight and expressive

inwardness.

by EMI Records

The Roumanian Dinu Lipatti is a myth among pianists, a cult figure ringed by the aureole of a reputation. The recording of Robert Schumann's Piano Concerto is one of those of which words like "imperishable" and "unsurpassable" are used, and it is the epitome of supple elegance; some of his Chopin performances exert the spell of "Romantic Schwarmerei" ; his interpretations of Bach are heard with respect but the listeners shake their heads over the perpetuation of 19th-century taste. And they lament Lipatti's Schubertian fate, his early death at only 33. The very sound of Dinu Lipatti's name is a distant, oh so distant sound from a remote age in the history of piano-playing.

Lipatti's contemporaries, musicians of the generation born during or just before the First World War, seem close to us-. Yehudi Menuhin (born in 1916), Sviatoslav Richter (1914), Annie Fischer (1914), julian von Karoly (1914), Wolfgang Schneiderhan (1915), Benjamin Britten (1913) and Nikita Magaloff (1912). The same is true of conductors born in 1912 (Sergiu Celibidache, Sir Georg Solti, Gunter Wand) and 1914 (Rafael Kubelik, Ferenc Fricsay) - but Dinu Lipatti, born in 1917, belongs for us to the remote past. It isn't difficult to work out why: he was scarcely able to travel at all, for the world was in turmoil in his day; his recordings first came out just as mono was giving way to stereo; and the opinion. formers in matters pianistic, Harold C. Schonberg (The Great Pianists, New York, 1963) and Joachim Kaiser (Grosse Pianisfen in unserer Zeit, Munich, 1965) clearly do not include Lipatti among the central pianists of the 2rth century, for Schonberg only briefly mourns the loss of a player who "might have been" one of the greatest of the century, and Kaiser occasionally mentions his name but does not grant him a chapter to himself in an otherwise loquacious book.

Where does the key to Lipatti's art lie? Not in the fluency, accuracy and high technical standard, for every aspiring pianist has those today, as a matter of course. In the breadth of his repertory (even if it excludes Beethoven)? It's not uncommon. In the poetry and expressiveness of his attack7 A large number of presentday pianists equal him in that. I never had the good fortune to hear Lipatti in the concert hall; I know him only through his recordings. Yet I will venture the theory that the key to Lipatti's art lies in something that reference books pass over: in the fact that he was a composer and also a conductor, just as his compatriot and godfather George Enescu was a violinist and a composer.

Composers who were also piano virtuosos were common enough once, but the species has almost died out in the 20th century. Pianists' compositions spark only a polite smile. A composer's craft is learnt mostly from analyses of works composed in the past or in the present day. Such analyses are available in books: Hugo Riemann and Jurgen Uhde on Beethoven's piano sonatas, Hugo Leichentritt's analyses of piano works by Chopin.

When I heard Lipatti's interpretation of

Chopin's B minor Sonata and the Barcarolle, I was

struck by a thought that has visited me only very rarely in my 50 years as a

critic: the man at the keyboard must have read Leichentritt and taken him to

heart, andlor have arrived at the same conclusions as Leichentritt's after

making his own analyses. The music is being played by someone who knows

composition from the inside, who knows what composing is from his own

experience. At the same time his artistic impulse is too strong to let him play

analytically: that is to say, thera is nothing at all dry, pedantic or

schoolmasterly about it. Playing the piano "analytically" was in fashion for a

while, around the time of Lipatti's death in 1950. One sober, unvarying dynamic

served for a whole piece, rattled off without pedalling, and credence was given

to the notion that Bach's partitas and suites should be cold-hammered because

Bach rarely or never specified dynamics. The "Urtext" was taken as the only road

to salvation. It was almost a capital offence to play Bach on a modern grand

piano instead of a harpsichord.

Dinu Lipatti's performance of the

B flat major Partita, BWV B25, renders the question concert grand

or harpsichord meaningless. There is no mechanical playing anywhere, every bar

is sustained by subtly graded but by no means arbitrary dynamics and ornamented

as if by an engraver's needle; every bar lets each of the two or three parts be

heard equally richly, is shaped by the crescendos and decrescendos, brings out

each change of direction in the part-writing expressively, not pedantically.

Bach's stylised dance forms are thick with repetitions, to which Lipatti brings

an inexhaustible aural imagination. Each repeat has a different colour,

different accents, sometimes even different tempos. The repeat marks correspond

to the conventions of Bach's time, but they do not signify mindless repetition.

The Gigue in its 121B motion is a miracle of the arts of repetition and

intensification; intended as a showpiece. it lives by the quality of the attack

and by the rhythm. The Partita brings us to the question of the pedal, but it

scarcely arises in Lipatti's case. lts immaterial, when he uses it and when not.

One does not think about it when listening to Lipatti. for one is spellbound by

the expressive abundance of colour and does not waste time attending to

technical details in the playing.

Guides to piano music testify to the

heroism and tragic melancholy in Mozart's A minor Piano Sonata K.

310. The work is rarely played in the concert hall, but if you should

catch it. you may not be very aware of the daemon invoked by the writers, for

it's only Mozart" being played. Lipatti goes a big step further, and shows how

he would have played Beethoven. if he had lived long enough to do so. Purists

tut-tut at dramatised subordinate voices, others find the maestoso of the first

movement over-emotional and the Andante too much "con espressione," as Mozart

marks it. But as the presto Finale whisks past like a shadow it comes to a

climax: the entry of the maggiore section. with an A major sounding more painful

and sorrowful than the fatalistic shadow-play in the preceding and following

minor sections. Instead of consolation the change to the major key brings

greater sorrow.

Lipatti is essentially a product of the Paris School. This can be heard in his performances of Chopin and Ravel as well as in the Schumann concerto. His teacher, Cortot. who died in 1962 at a great age, left behind him not only recordings but also written testimonies from which we know his views on music. We can tell that Lipatti took to heart much of what Cortot said about the interpretation of Chopin: first of all the intensifying and breathing of melodic life into sequences of quavers that appear to flow on heedlessly, the constancy of the underlying pulse. leggiero playing (the Scherzo in op.58), the Bellini-like cantilenas in the main melody of the Largo and the second subject of the first movement in op. 58, the 12/8 of the unhurried Barcarole, and the goal-directed logic in the Presto ma non tanto of the Finale of the B minor Sonata.

Lipatti - achieves his breathtaking effect in this finale by the simple trick of taking the Presto non tanto literally non tanto. It's all that's needed for the movement to reveal its own face. in fact Lipattis French ancestry can be traced back still further to Chopin himself. A tradition has I it that Chopin began his D flat malor Nocturne op. 27 No.2 pianissimo and una corda, which is not how it is marked in various editions. Lipatti begins this lyrical "night-piece" as delicately as breathing. Either he knew of the tradition or he followed in Chopin's footsteps instinctively. The selection on this issue includes Lipatti playing duets with his teacher Nadia Boulanger in the four-hand original version of Brahms's Waltzes Op. 39. For all the charm on show there is nothing here of the "innocent little waltzes in Schubertian form" to which Brahms whimsically referred: teacher and pupil bring to them vigorous attack, ardent engagement and strict rhythm. Brahms the modernist, without his whiskers.

Lipatti moved into a French domain to

record Ravel's Alborada del gracioso, the dawn song of a court

fool. He executes the rapid repeated notes, the hairraising glissandos in thirds

and sixths, the imitation of guitars and castanets with complete clarity and

none of the usual sfumato. The left hand realises the bass lines powerfully - no

"impressionist" mistiness here. We realise that pieces like this were played

much more juicily and scurrilously in their place of origin, Paris, than is

commonly supposed.

The recording of Schumann's Piano

Concerto under Karajan was made in the postwar period . It's hard

to see why this performance is famed above all for its elegance. It is an

uncommonly virile, dramatic interpretation of the most famous of Romantic piano

concertos, free of any perfumed airs, heavyhandedness or conventionalism. A

composer-like intelligence analyses the complex form and denies itself any

injection of subjective vanity in the collaboration with its orchestral partner.

The start of the Allegro affettuoso is just that: the expression of affects. The

middle movement, called Intermezzo, is an Andante grazioso with light staccatos

and melodic grace, not a brooding or even sentimental nocturne. The opening

chords of the Finale gleam like fanfares. Muscular octaves demonstrate the

strength of Lipatti's left hand. The modifications of tempo or dynamics do no

violence to the music. Altogether, Lipatti makes a younger impression on me in

the Schumann concerto than in any other recording: a hothead, a daredevil, a

reckless recruit to the League of David, going to war against the

philistines.

The young professor at the Geneva conservatory, where Liszt had been a most distinguished Ippredecessor in the mid-1830s, also recorded a work that owes much to Schumann's example, Grieg's A minor Concerto, in a performance conducted by Alceo Gallieta. Lipatti remains the dominant figure, even in the Adagio, where the piano has nothing very much to say. The nale, a Norwegian leaping dance above fifths in the bass. has sharply defined rhythmic contours and a driving elan; the second subject in F major is introduced in a conspicuously moderated tempo without allowing its folk character to slide the short distance into sentimentality. The pianist tackles the Grieg concerto as a virtuoso showpiece. on the assumption that that is the only way to rid it of the odium of repainting Schumann in Norwegian colours and rescue it for our times.

It is not only in Schuberts Impromptus D. 899 Nos. 2

and 3 that we can observe one of Lipatti's characteristics. He scarcely

ever yields to the pianists bad habit of letting the bass sound a fraction

earlier coquettishly delaying the first beat of the bar in the melody. As

a composer he disapproves of this solecism committed by pianists who are only

pianists. As a result the G flat major Impromptu is free of

intrusive effects and can present itself as a simple scena. Many highly

respected pianists take this Andante more slowly and give the melody above the

quaver triplets a more emotional and visionary tone.

Young Lipatti knew nothing of our compulsive need to see the abyss of

despair behind every bar Schubert wrote. His Schubert remains simple, expressive

and of this world rather than the next. The E flat Impromptu gives

a lesson in how to shape a perpetuum mobile from quaver triplets which ripple

along like an etude. and how to erect a rocklike middle section to resist it.

Schubert may seem close to Chopin here, but Lipatti emphasises the difference:

when Schubert approaches the étude he retains a classical formal framework, but

Chopin takes off in swirling fantasies It is much to be regretted that Lipatti

left no of Schubert's Sonatas.

One of these recordings made performance

history : Lipatti's performance of Bach's

Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring in

the version by Dame Myra Hess. The work, the version and the performance

are sublime, beyond words. Lipattis playing expresses an inner calm. The melody

grows out of its setting without any special emphasis. Three minutes in musical

paradise.

EMI RECORDS Translation: Mary

Whittelt

Speaking in a recent television interview the Canadian

novelist Margaret Atwood rejoiced in the absence from her novels of human

paragons. Even granted their existence, such people, she felt, would make poor

or unrewarding characters. Yet had she met and heard Dinu Lipatti (1917-1950)

she might well have altered her view. For Lipatti possessed both the qualities

of a saint and a richly human nature, striving throughout his painfully short

life for an ever closer embrace or identification with his chosen composers. For

Yehudi Menuhin he was a manifestation of a spiritual realm, resistant to all

pain and suffering'. Cortot thought his playing 'perfection' while Nadia

Boulanger (Lipatti's 'musical guide and spiritual mother') was haunted, like so

many others, by 'that serene face with its dark velvet eyes' and the musical

clarity and force that emanated from his being. Poulenc, too, spoke of 'an

artist of divine spirituality' while Lipatti's close friend and compatriot, the

pianist Clara Haskil (who quickly became, in his teasing and aftectionate

letters, his 'Dear Clarinette') wrote to him in wonder and

admiration:

'How I envy your talent. The devil

take it. Why must you have so much talent and I so little? Is this justice on

earth?'

Lipatti countered such eulogy with

extreme modesty, with comments such as 'the concert went quite well'. He was, to

quote Haskil once more, 'a man who seemed embarrassed by his own genius'. He

fulfilled a startling variety of roles-as pianist, composer, teacher and

critic-with tireless devotion and integrity despite the early and relentless

encroachment of the leukaemia that finally killed him. His compositions are less

familiar than they should be, but his classes in Geneva became legendary, and

his reviews, including a brilliantly qualified estimate of Horowitz and a gentle

but firm placing of artificial expression (of the indulgent demi-teintes

cultivated by some pianists), were as acute as they were sympathetic. His

statements on the 'cult of authenticity' and on the sacredness of the composer's

score should be read by all serious musicians. Yet it is as a pianist that he

will always be remembered. For him the 'craft of his metier' was always a

blessing rather than a burden and, in exultant reference to the piano, he once

exclaimed:

"If you only knew how much I love

'him Lipatti's final recital is one of the great

musical and human statements, a testimony to his transcendental powers,

his almost frightening assertion of mind over matter. Ignoring his doctor's

advice, Lipatti honoured his last engagement seemingly against all odds, bidding

farewell to his adoring public in a unique display of perseverance and musical

insight. The only concessions to what his wife descri bed as 'a real Calvary'

were the omission of Chopin's A flat Waltz, Op. 34 No.1, and of a repeat in the

C sharp minor Waltz. These, together with an occasional hint of coolness-like

the settling of some fine but unmistakable frost-in some of the gentler Waltzes,

are the only evidence of Lipatti's state.

How

touching is the introductory flourish in both the Bach and the Mozart, a

momentary but necessary flexing of muscles and a stabilising focus rather than

an old-fashioned gesture. And although these performances have been endlessly

discussed and analysed their quality lives on, increased rather than diminished

by time. How puzzled Lipatti would have been by the idiosyncratic Bach of more

recently celebrated specialists, by the apparent need for intervention; as if

the composer needed help rather than illumination. Few performances of the First

Parfita are more radiant or economical than Lipatti's. And then there is

Lipatti's Chopin where the ultra-critical Toscanini glimpsed a musical ideal

('at last we have a Chopin without caprices and with the rubato to my liking'),

a truly aristocratic response to music 'in which emotion is permitted to suggest

itself only through a veil of elaborate civility'. Lipatti's way with the

Waltzes has justly acquired legendary status. His Schubert Impromptus, too, are

flawless examples of his technical and musical regality, the G flat a

full-bodied alternative to a more attenuated or whispering magic, the E flat

with a final touch of defiance rather than deference (Schubert like Lipatti died

in his early thirties, a victim of illness and adversity).

Lipatti's repertoire was more extensive than is commonly

realised and radio recordings of, say, Ravel's G major Concerto and, possibly,

Beethoven's Waldstein Sonata, are as elusive and as eagerly sought as star-dust.

But what we have is of classic strength and status. This final and unforgettable

Besanon recital is, indeed, living confirmation that 'God lent the world His

chosen instrument, whom we called Dinu Lipatti, for too brief a space' (Walter

Legge).

© BRYCE MORRISON, 1994

http://humboldt1.com/~mimicry

http://www.nd.org/jronsen/dumitrescu.html